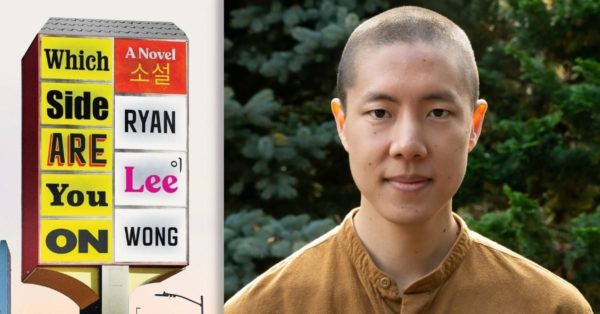

I met Ryan Wong in April at the Branching Streams Conference in Austin, Texas, which Ryan attended in his role as Director of the Brooklyn Zen Center. When I learned that he is a writer as well as a Zen student, the idea for this interview arose. His novel, Which Side Are You On, was published by Catapult Books on October 4, 2022.

Ryan first had the idea that sparked his novel around 2015 when he was living in Brooklyn, NY, and was involved in the Black Lives Matter movement. A pivotal moment was the event involving Peter Liang, a Chinese American police officer who shot and killed Akai Gurley, an unarmed Black man. It was shocking to Ryan how many Chinese Americans supported Gurley, and how this caused a huge rift in the Asian American community.

Although Ryan had known that his mother had been involved in Black-Korean organizing in the 1980s in L.A., that work had been overshadowed by the 1992 uprising. He wanted to learn some history and decided to write a novel because “fiction is a way to tell a story without taking a side. I could explore the more emotional and social sides of the story.”

What interested Ryan is that both his parents had been long-time activists, community organizers, and teachers and they had made a conscious effort not to speak about their politics or impose them on him. Some of their friends had tried to involve their children in politics, but they didn’t like going to protests and meetings with their parents and took more conservative paths.

Many of his parents’ activist experiences had been difficult and painful, hard to explain to a young child—for example, some of their friends had been murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in 1979. Both Ryan and his parents had to be ready to share these stories.

In writing the novel, Ryan considered ways to engage his potential readers. “The main thing I had to create was dramatic stakes for the main character. It doesn’t come naturally for me. A reader doesn’t have any investment in opening a novel. You have to tell them what the stakes are for the character. In Zen language, Reed, the protagonist, has to see the image of himself as a successful activist crumble.”

Ryan attended an MFA program in Fiction Writing at Rutgers from 2017 to 2019 to immerse himself in reading fiction and learn the craft of writing. He and his fellow students took apart famous stories and each other’s stories. “If you’re doing your job well as a writer, all of that is hidden from the reader. Your job is to make the machine work, so the reader doesn’t have to think about it.”

His Zen practice and his writing practice are inseparable. “I can’t picture one without the other. I see my writing practice as Eihei Dogen’s teaching, ‘To study the self is to forget the self.’ Writing is one of the ways I can see my karma and articulate it. As soon as I see my karma, I’m changing. In fiction, one character can illustrate this process. As soon as they learn something about themself they have to choose whether to hold on to that identity or let it go.” At the start of the novel, the main character, Reed, who is very entrenched in his political beliefs, often alienates the people close to him with his self-righteousness.

Ryan sees writing as a compassion practice. “If I’m not able to be compassionate toward my characters the writing suffers. The hardest character was Reed. Six years ago I was more like Reed than I am now. For me it’s often hardest to be compassionate with people who are going through what I recently went through. It involves turning toward part of myself that has been hard to accept. But there’s no turning away. As soon as you turn away, the reader can tell. As readers, we have very sophisticated truth detectors. We want the writer to be honest.”

Ryan spoke about the ways in which the novel explores generational trauma. “A key component of the plot is Reed’s understanding of his inheritance. He’s not just an individual. He’s tied to this particular ancestry. In the beginning he sees himself as an individual and makes choices from that place. As the novel goes on, he still has to make choices, but it’s from understanding his family’s history, Korean history, a history of organizing and struggle. Learning about this from his parents entirely changes his world view as well as his view of his parents.”

I asked whether Ryan writes poetry. “As fiction writers, we’re trained to be specific, to capture details. Even though a novel is long, it’s made out of sentences. Poetry shows you how to do that—not waste words, be precise with language, build an image. A house should be made of solid bricks.”

Ryan spoke about the discipline it took to work on his novel in the midst of a full life. “A big part of finishing this novel was building a writing routine. Between 2016 and 2019 I tried to write every single morning. At first, writing takes a lot of practice—like preparing for a long run or learning to play an instrument.” He wrote the final draft during the summer of 2020 while following the monastic schedule at Ancestral Heart, Brooklyn Zen Center’s country temple. Though the schedule began early in the morning, there was a two-hour break in the afternoon. “I’d swim in the quarry, think about what I would write, then type it out for half an hour or so.”

“Writing is a solitary practice, but for me it’s not lonely. At every stage I’ve felt community—the writing community, the arts community, and the sangha. The container and stillness and mirroring of sangha has been essential to my writing.”

This summer, for the third time, Ryan attended the annual retreat with Kundiman, an organization dedicated to providing a nurturing space for Asian American writers. “I learned to really give myself permission to be a writer at these retreats. Growing up, it didn’t occur to me that I could be a writer, because most of the books I read in school were by long-deceased European writers. I didn’t know many writers, let alone Asian American writers. It was essential to be with peers who were doing just that. The world of books is so much more diverse than it was twenty years ago. It’s exciting to be a writer now. It feels like it’s part of being a wave or a movement.”

Before Ryan began writing fiction he was an art critic and was more comfortable with non-fiction. Since finishing Which Side Are You On he has written some essays and personal reflections and a short story about a character who is just starting to meditate and is struggling with his mind.

This Spring, Ryan left the monastery and returned to Brooklyn. “Back in Brooklyn the myriad things are coming up all the time. I’m a different person than before my two years of training at Ancestral Heart. I have more grounding and stability. It’s more fun now to be in New York, because if there’s a place that doesn’t conform to your preferences, it’s New York City.”

Before beginning Zen practice with Brooklyn Zen Center in 2015, Ryan tried a few other Dharma centers. “I stuck with Brooklyn Zen Center because I was attracted to the mix of social engagement and dharma.” His teacher is Kosen Greg Snyder, from whom he received the precepts in Fall 2019. His dharma name is Churyu Hongo / Faithful Dragon, Original Home.

Ryan will give a reading at San Francisco’s Booksmith on Haight Street on November 7. For readings in New York, Los Angeles, and other venues see his website.